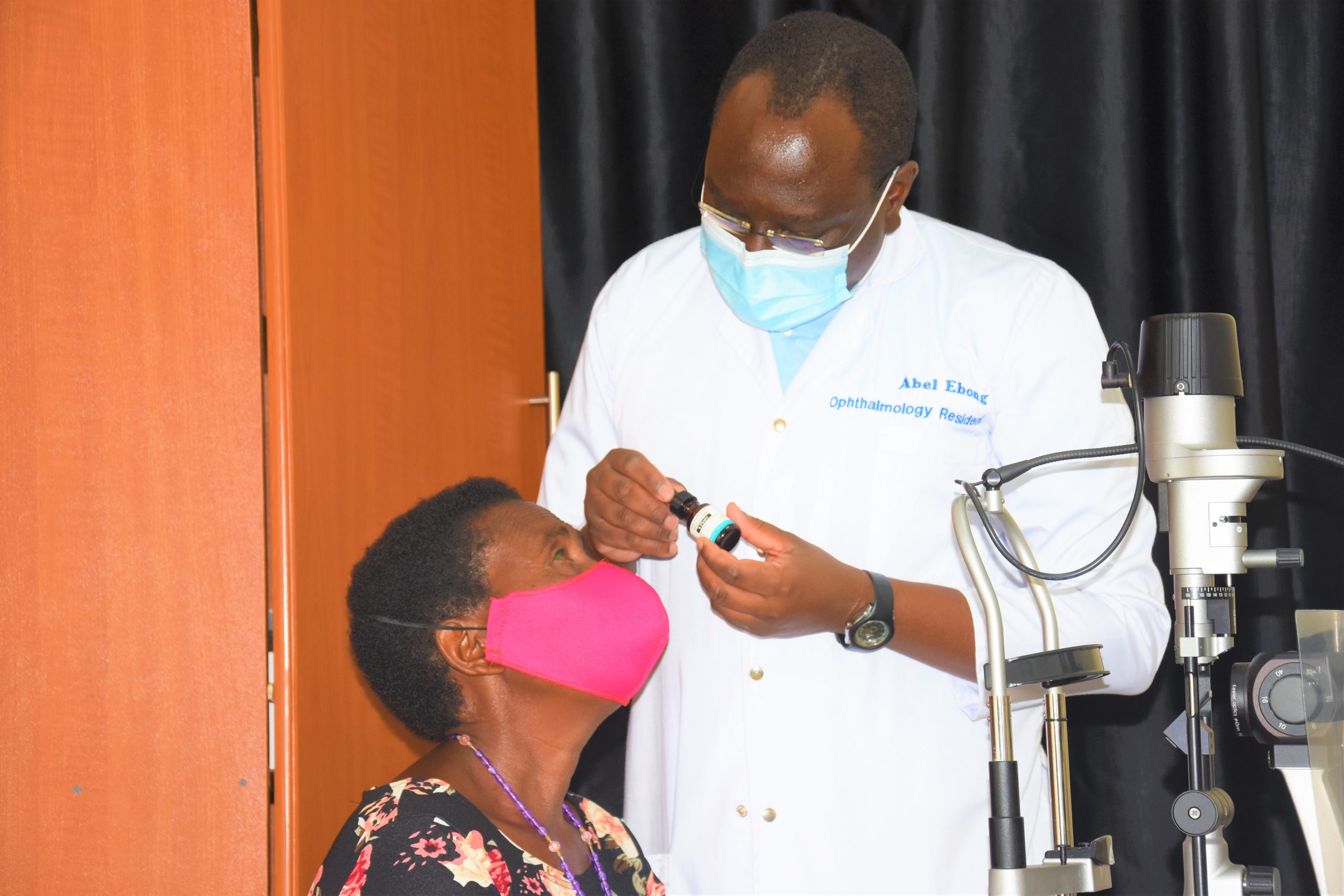

Dr Abel Ebong, one of the registrars at Mbarara University tertiary eye hospital in Uganda administers Chlorhexidine eye drops to a patient with Fungal Keratitis

A new treatment option for a potentially blinding disease has shown promise in a sub-study in Uganda.

Keratitis is an inflammation of the clear tissue at the front of the eye, known as the cornea. When caused by a fungal infection, it can be extremely painful and can even lead to the loss of an eye. Globally, the incidence of fungal keratitis (FK) is estimated to be more than one million cases per year, representing a significant public health concern when potential blindness is taken into account. It is particularly common in lower-income countries and amongst manual labourers such as farmers who are prone to damaging their eye, leading to infection.

The current standard treatment for FK is the antifungal natamycin, delivered in eyedrops. However, the drug is not effective in all cases, with some on treatment progressing further towards blindness. Additionally, natamycin is not readily available in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and is relatively expensive.

A research team led by the Mbarara University of Science and Technology in Uganda and the International Centre for Eye Health decided to investigate a different treatment, chlorhexidine gluconate, as part of a wider study on the disease. The sub-study followed pilot trials in South Asia which suggested that chlorhexidine could be equally or more effective than natamycin. It was also known that in Uganda, the majority of keratitis cases are caused by fungi, and the outcomes for fungal infections are more likely to be worse.

Participants in the original keratitis study who were not responding to natamycin (5%) were given an additional treatment with topical chlorhexidine (0.2%). Following up with the patients, 75% of those who had been deteriorating on natamycin alone showed signs of responding after receiving chlorhexidine, with ulcers caused by the infections healing and inflammation subsiding. Whilst a small case series, the results show that chlorhexidine could be a viable further option for patients with these infections who are not responding to treatment. Additionally, the chlorhexidine used in the study was 15 times cheaper than natamycin, making it a practical option which warrants further investigation. With few current available FK treatments, further research following this study has the potential to improve care for FK patients.